Saxon Montacute

Saxon Montacute: A Glimpse into Early History

Montacute, previously known as Logworesbeorgh, holds a rich Saxon history, though evidence of Saxon structures in the village remains elusive. Life in this region during Saxon rule likely resembled that under Roman and Celtic influence, with most inhabitants living in timber houses. This page delves into Montacute's Saxon past, tracing its connections to the Roman occupation, early Saxon invasions, and the cultural shifts that followed.

The arrival of the Saxons

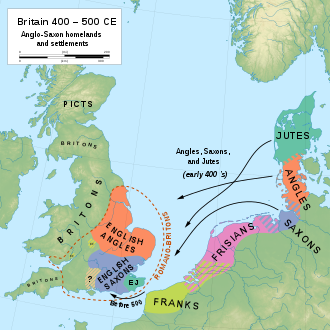

By the late 7th century, the Saxons had likely settled in South Somerset. Before this, the Celtic Durotriges tribe lost Ham Hill around 45 AD to the Roman second legion under the future Emperor Vespasian. During the Roman occupation (43-410 AD), Montacute became Romanised, as evidenced by local villas, while the Celtic Dumnoniae to the west may have resisted Roman influence and remained self-governed, possibly expanding into former Durotriges territory after the Romans departed and refortifying Cadbury Castle (Wikipedia). Around 540, Gildas wrote 'On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain'. Although the earliest surviving manuscripts date to the 11th century, in 731 Bede used an earlier version for his Ecclesiastical History of the English People (written from Jarrow in Northumbria,) and a surviving copy of this dates to about 737. These texts describe how, around 455, Saxons led by Hengist and Horsa were invited by Vortigern to defend Britain against the Picts and Scots, but eventually turned on their hosts. In the West Country, the Romano-British Celts likely resisted Saxon advances until the mid-6th century or later. Although Somerton (12 miles north of Montacute) became the capital of Wessex in the 10th century, in the 6th and 7th centuries the founders of the House of Wessex, the West Saxon Cerdicing dynasty, was centered in the Upper Thames Valley. Bede often refers to them as the Gewissae. Cerdic (ruled 519-534) arrived in Southampton around 495 with his son or grandson Cynric, and descent from Cerdic became a key qualification for later Wessex kings and subsequent rulers of England and Britain

Establishment of Saxon rule in the West Country

Writing in the 12th century, historian Henry of Huntingdon records that after the fall of Roman Britain, with the incursion of the Germanic tribes England became loosely divided into seven main regions of influence (the Heptarchy) of Wessex, Sussex, Essex, Northumbria, Mercia, East Anglia and Kent. Wessex and Sussex were strongly influenced by Saxon colonisation (see map above from Wikipedia). Wessex remained centred in the Upper Thames Valley through several West Saxon rulers, including Cynegils (ruled 611-642) who converted to Christianity and was buried in Winchester Cathedral. Saxon influence gradually spread south-west and Centwine (ruled 676-685) was the first Saxon patron of Glastonbury Abbey, while King Ine (ruled 688-726) was the founder of Muchelney Abbey, just 9 miles north-west of Montacute. King Ine had his main palace at Winchester but there are also records of a temporary palace 6 miles west of Montacute, at South Petherton; the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says he also controlled Somerton but it was lost again to the Mercians after his rule. King Ine created the first Code of Laws for the West Saxons (Aethelbert King of Kent had written a Code of Law almost 100 years earlier) and introduced shires and ‘shire courts’, he made sub-kings 'ealdormen' in charge of the shires, and introduced ‘church-scot’ payments, precursor of tithes.

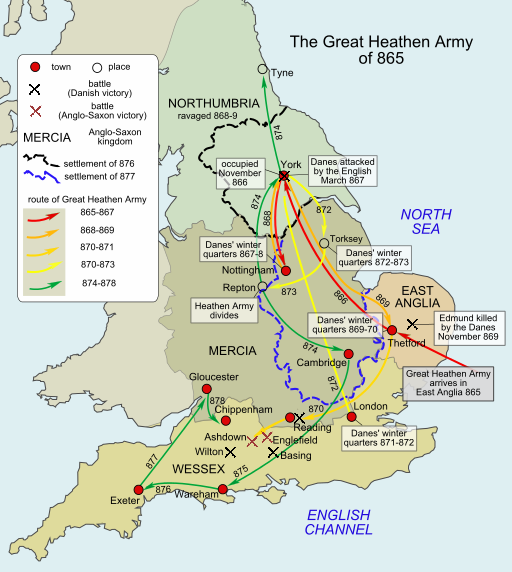

Image from Wikipedia: Invasion of The Great Heathen Army

By the 8th century the heptarchy had consolidated into the four kingdoms of Wessex, Mercia, East Anglia and Northumbria. Viking raids became more frequent and in the 9th century a combined Scandinavian force, the Great Heathen Army, marched through East Anglia and Mercia. Halfdan Ragnarsson, Ivar the Boneless and Ubba led the army, possibly to avenge the death of their father, Ragnar Lodbrok, in an earlier raid. Æthelred King of Wessex died in 871 and was succeeded by his brother, Alfred the Great. King Alfred's defeat of the Vikings at the Battle of Eddington in 878 marked the start of the process which would eventually unify England under a single ruler, Alfred's Grandson, Æthelstan.

The Saxon Language

Some of the Saxon language can still be heard in traditional Somerset dialect. King Alfred was King of the West Saxons 871 to 886 and of the Anglo-Saxons to 899; he translated books including Bede's Ecclesiastical History and wrote his Anglo-Saxon Chronicle in the Early West Saxon language of the late 9th century. This evolved until the time of the Conquest but can still be heard, especially in the use of the verb 'to be' (I be, Thee bist, He be, We be, Thee 'rt, They be) (Garton, 1971)

Early Charters relevant to Montacute

From Saxon times there are records of Charters recording property ownership and rights. Many now only exist as copies, or are referenced in other early works; a list of Charters can be found online in the Electronic Sawyer database.

The following references to Montacute and neighbouring villages are listed in ' The Early Charters of Wessex' (Finberg, 1964):

1. (Not in Sawyer) Finberg 358. ? 676 x 685 King Baldred to Glastonbury Abbey. 16 hides at Logworesbeorh. LOST. Dugdale, p50; Johannis .... Glastoniensis Chronica sive Historia de Rebus Glastoniensibus, ed T. Hearne. Oxford 1726 Vol I p41. (Baldred was one of the petty kings of Wessex, who held power with or under Centwine, before Caedwalla subdued the latter and acquired supremacy in 685.)

2. (Not in Sawyer) Finberg 390. 760 x 762 Cynewulf, King of the West Saxons, to Guba, abbot of Glastonbury. Huneresburg ((Houndsborough) on the east bank of the R. Parrett. LOST

3. Adami de Domerham Historia de Rebus Gestis Glastoniensibus, ed T. Hearne. Oxford, 1727 pp63, 98. Houndsborough, which at one time gave its name to a hundred, is now represented by Houndston in the Parish of Odcombe. -Collinson, History of Somerset II, p323.

4. S303; Finberg 408. 854 *Aethulwulf, king of the W Saxons, to Glastonbury Abbey, exemption from all secular dues of 5 hides at Bokland toun (Buckland Newton), 6 hides by Pennard, 1 hide at Cotenesfellda, and at Cerawicombe (Crowcombe), in pursuance of his resolve to enfranchise a tenth of the land in his kingdom for ......Dated Wilton, Easter Day (22 April).

The fuller text of this charter printed The Great Cartulary of Glastonbury, Ed. A. Watkin. Somerset Record Society LIX (Vol I) p143 gives Cetenesfeld in place of Cotenesfelda (where Adami de Domerham Historia de Rebus Gestis Glastoniensibus, ed T. Hearne. Oxford, 1727 p69 has Occenefeld) and enumerates other lands as 6 hides at Cerawycomb, 10 at Sowy (Zoy), 3 at Piriton (Puriton), 1/2 hide at Lodegaresbergh (Montacute), 1/2 hide "be del", besides 3 places in Devon. Adami de Domerham Historia de Rebus Gestis Glastoniensibus, ed T. Hearne. Oxford, 1727 p69 adds Duneafd (Downhead). On Aethulwulf's 2 decimations, see Ch VI.

5. S1703; Finberg 414. 871 x 879 Tunbeorht, bishop (of Winchester), to Glastonbury Abbey,. Logderesdone (Montacute). LOST

Johannis .... Glastoniensis Chronica sive Historia de Rebus Glastoniensibus, ed T. Hearne. Oxford 1726 Vol II p371, from the Glastonbury Landbok.

6. S1717; Finberg 430. 924 x 939 King Athelstan to Aelfric. Stoke. LOST. Johannis .... Glastoniensis Chronica sive Historia de Rebus Glastoniensibus, ed T. Hearne. Oxford 1726 Vol II p371, where it is recorded that Aelfric subsequently gave the land to Glastonbury. Adami de Domerham Historia de Rebus Gestis Glastoniensibus, ed T. Hearne. Oxford, 1727 p71 states that the Abbey received a gift of 5 hides at Stoka from a widow named Uffa (?Aelfric's widow). Perhaps Stoke under Ham (Estochet), which was thegnland of the abbey in 1066. Bates, SANHS XLV (2), 1899 pp74-75.

7. S1728 451. 939 x 946 King Edmund to Wilfric. Tintanhulle. LOST

Johannis .... Glastoniensis Chronica sive Historia de Rebus Glastoniensibus, ed T. Hearne. Oxford 1726 Vol II p371 from the Glastonbury Landbok. Adami de Domerham Historia de Rebus Gestis Glastoniensibus, ed T. Hearne. Oxford, 1727 p73 adds that it was 5 hides, left for his soul-scot.

8. S1779 521. 979 x 1016 King Ethelred to the thegn Godric. Stoke. LOST

Johannis .... Glastoniensis Chronica sive Historia de Rebus Glastoniensibus, ed T. Hearne. Oxford 1726 Vol II p373, from the Glastonbury Landbok. In 1066 Stoke-under-Ham and Stoca Dreycote were held as thegnlands of the Abbey.

9. 529. 1032 (Cnut confirms priviliges granted to Glastonbury Abbey by previous kings)

10. 561. query whitcombe? Dugdale, W in Monasticum Anglicum Ed J. Caley and B. Bandinel 6 vols in 8, 1817-30 p337

Note for further research: Ref Finberg p201 and 211 King Aethulwulf's decimations CHECK The Great Cartulary of Glastonbury, Ed. A. Watkin. Somerset Record Society LIX (Vol I) p143

The first documented reference to Montacute in Saxon times

The first documented reference to Montacute in Saxon times is in a (lost?) Charter recorded in Malmesbury's 11th century De Antiquitatae Glastonie Ecclesie (On the antiquity of Glastonbury Church); John Scott’s analysis of its surviving manuscripts says Malmesbury wrote

’38. De Baldredo rege qui dedit Pennard et Muntagu’: ‘Anno Dominice incarcionis DCLXXXI Baldred rex id est Pennard Penger vi hidas, Logworesbeorh xvi hidas, et capturam piscium in Pedride Hemgislo Abbati…’.

Scott translates this as

’38. On king Baldred who gave Pennard and Montacute’: ‘In 681 AD King Baldred gave 6 hides at Pennard, 16 hides at Ludgersbury and fishing rights to the Parrett to Abbot Haemgils….’

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a 9th century retrospective diary of important dates that was probably commissioned by King Alfred to promote reunification of England and possibly in part written or dictated by him. It gives a contemporary record of King Alfred's resistance against the Danes, and distributed copies of the manuscript were updated and sometimes interpolated. Its earliest Chronicles refer to locations near Montacute including Wigborough (a hamlet just 5 miles west), leading to the suggestion that it was written not so far from Montacute!

F. M. Stenton ('The South-Western Element in the Old English Chronicle' (1925)) says

the suspicion that the chronicler’s interest lay in the south-western shires is materially strengthened by the annal for 845, which tells how the ealdormen of Somerset and Dorset defeated the Danes at the mouth of the Parret, and by the annal for 851, which opens with the record of a victory won at Wigborough in the west of Somerset 1 by Ceorl the ealdorman of Devon.

AD878 The Saxons are forced into the Somerset marshes. Alfred goes into hiding – hence the legend of the burnt cakes. Alfred raises an army and defeats the Danes at Edington. Under the subsequent treaty of Wedmore, Guthrum, the Danish King, and the Danes convert to Christianity with Alfred as Guthrum’s Godfather.

The same treaty creates the Danelaw, which divides the country into two regions. This suits most Saxons other than those from East Anglia and Essex, for as one of the boundaries is the river Lea, they cannot return!

From 886 to 899 Alfred is King of all England; the Welsh monk Asser was recruited to Alfred's court and then placed as Bishop of Exeter then Sherborne; while there he wrote The Life of King Alfred (Vita Ælfredi regis Angul Saxonum) and a copy from about 1000 CE (Cotton MS Otho A XII) survived until the fire of 1731. A digitised copy of a 16th century transcript can be viewed online at the British Library, http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Cotton_MS_Otho_A_XII/1.

AD1016 After Alfred’s death, various kings have control of some or all of England, until Canute (Cnut) once more unites the country under one ruler. He moves his court to London, where he was crowned in 1016.

King Baldred was probably a sub-King of Centwine (r.675-685). Malmesbury's reference that includes Montacute may refer to multiple charters; the Sawyer record for S 236 (681) is "Baldred, king, to Hæmgils, abbot, and the church of Our Lady and St Patrick, Glastonbury; grant of 12 (or 6) hides (manentes) at Pennard, Somerset"; for S 1665 (676 x 685): Baldred, king, to Hæmgils, abbot; grant of a fishery in the river Parret"; and for S 303 (854): Æthelwulf, king of Wessex, [was king 839-858] to the Church; general grant of lands and privileges with a list of the Glastonbury estates affected, namely 5 hides at Buckland Newton, Dorset; 6 at Pennard, Somerset; 1 at Cetenes felda; 6 at Cerawycombe (? Crowcombe, Somerset); 10 hides at Sowy (cf. Middlezoy, Westonzoyland), 3 at Puriton, 1.5 at Montacute (Lodegaresbergh), Somerset; 1.5 at Culmstock, 0.5 at Monk Okehampton and 0.5 at Braunton, Devon ('Second Decimation')."

In T Hearne's 1726 publication we find:

References:

Johannis .... Glastoniensis Chronica sive Historia de Rebus Glastoniensibus, ed T. Hearne. Oxford 1726; Joannes of Glastonbury has abbreviated the Historia de rebus gestis glastoniensibus of Adam of Domerham for the period 1126-1291 and continued it to about the year 1400. Included also is the later continuation to the year 1493 (Ashmole MS. 790, Bodleian library) written perhaps by the monk Thomas Watson.

Paged continuously.

List of Saxon Monarchs:

| 519 | Cerdic |

| 534 | Cynric |

| 560 | Ceawlin |

| 591 | Ceol |

| 597 | Ceolwulf |

| 611 | Cynegils |

| 626 | Cwichelm |

| 643-645 | Cenwalh |

| 645-648 | Penda |

| 648-672 | Cenwalh |

| 672-674 | Cenwalh & Seaxburh |

| 674 | Cenfus |

| 674-676 | Aescwine |

| 676-685 | Centwine |

| 685-688 | Caedwalla |

| 688-726 | Ine |

| 726-740 | Aethelheard |

| 740-756 | Cuthred |

| 756-757 | Sigeberht |

| 757-786 | Cynewulf |

| 786-802 | Beorhtric |

| 802-839 | Ecgberht |

| 839-858 | Aethelwulf |

| 858-860 | Aethelbald |

| 860-865 | Aethelberht |

| 865-871 | Aethelred |

| 871-886 | Alfred the Great |

| 899-924 | Edward the Elder |

| 924-939 | Æthelstan |

| 939-946 | Edmund I (the Elder) |

| 946-955 | Eadred |

| 955-959 | Eadwig |

| 959-975 | Edgar the Peaceful |

| 975-978 | Edward the Martyr |

| 978-1013 | Æthelred the Unready |

| 1013-1014 | Sweyn Forkbeard |

| 1014-1016 | Æthelred the Unready |

| 1016 | Edmund Ironside |

| 1016-1035 | Cnut the Great |

| 1035-1040 | Harold Harefoot |

| 1040-1042 | Harthacnut |

| 1042-1066 | Edward the Confessor |