Montacute's Legend of the Holy Cross

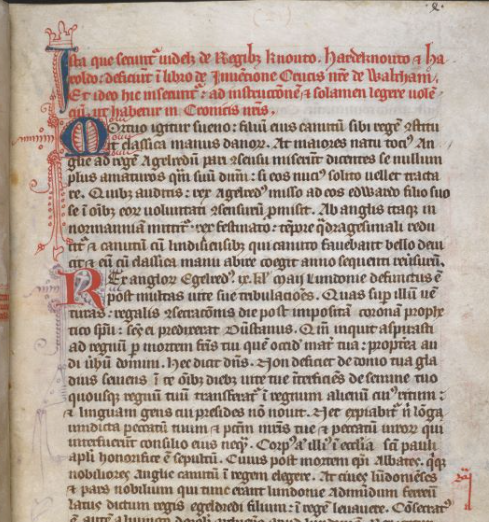

[Image shows a page from one of the surviving copies of the original manuscript. The text starts "Ista que secuntur uidelicet de Regibus knouto. Haedeknouto et harolo deficiunt in libro de Inuentione Crucis nostre de Waltham. ...."]

The Story of the Holy Cross

In the time of King Canute (King Cnut), the Danish king who ruled England from 1016 to 1035 and was known for consolidating power across England, Denmark, and Norway, a life-size stone crucifix, the Holy Cross, was dug up on Montacute Hill (St Michael's Hill) along with a smaller crucifix, a bell, and a black book ('Liber Niger'). Or so the story goes.

The Divine Visitation

The legend of this miraculous discovery was recorded in 1177 by one of the canons of a newly-founded Augustinian Priory at Waltham in Essex, 150 miles north of London. The story begins with a pious, God-fearing smith in Montacute who was visited one night by a divine figure. This figure commanded him to tell the priest that the villagers should fast, pray, and confess their sins before heading to the top of the hill to unearth a hidden treasure. When the smith woke, he dismissed the vision as a dream and did nothing.

A Second and Third Warning

The divine figure appeared again, warning of punishment if the smith did not inform the priest. Despite this, the smith consulted his wife, who was described as 'a foolish woman, quick to give thoughtless advice', and chose to ignore the warning. A while later he received a third visit and this time he was thoroughly rebuked; the divine figure gripped his arm so tightly he left finger-nail marks, proving it was no mere dream. Terrified, the smith went to the priest, and together they made preparations.

The Discovery on Montacute Hill

On the chosen day the villagers, joined by a great crowd, climbed Montacute Hill. At the top they dug down '40 cubits' (about 60 feet or 18 metres) until they found a massive stone, in the middle of which a gaping fissure appeared. They removed the debris and suddenly there appeared an image of the crucified Saviour, carved from 'black' stone (possibly Tournai marble or polished blue lias? ref Watkiss & Chibnall 1994). Alongside the crucifix were a smaller cross, a bell, and the 'Liber Niger' (latin for Black Book, thought to mean a book of the 4 Gospels).

The Sacred Relics and Tovi the Proud

Deeming the relics too sacred to touch, the villagers surrounded them with tents and sent for their lord, Tovi (aka Tofig) the Proud, King Cnut’s standard-bearer and right-hand man. Upon Tovi's arrival, the relics were transported to the 'churchyard on the floor of the valley.' The smaller crucifix was sent to the local church, while Tovi arranged for a cart drawn by 12 red oxen and 12 white cows to carry the larger cross and other relics. The animals refused to move until Tovi uttered the word 'Waltham.'

The Miracles at Waltham

Tovi transported the Holy Cross to his estate in Waltham, where miraculous healings began to occur. In response, Tovi built a church and established foundations for two priests. The church's first congregation included 66 individuals who had been cured by the Holy Cross and dedicated themselves to its veneration. Tovi adorned the figure with gold and precious stones, but when the first stud was set, the stone began to bleed. He hung his sword around the figure, and his wife contributed her gold crown and girdle and melted down her jewelry to create a foot-support for the Saviour. She even had a stone set into the foot-support which glowed in the dark; the stone’s value was so great that Henry of Blois, Bishop of Winchester, once offered 100 Marks for it, only to be refused

The Holy Cross's Role in History

After Tovi’s death, the Waltham estate came under the control of King Edward the Confessor, a ruler renowned for his devout nature and the construction of Westminster Abbey. Following Edward's death in 1066, the estate passed to King Harold Godwinson, the last Anglo-Saxon king of England, who reigned from January to October 1066. As a child, Harold had experienced a miraculous cure from paralysis attributed to the Holy Cross. Before marching south to confront William of Normandy at the Battle of Hastings, Harold stopped at Waltham to pray. During the battle, his troops rallied under the cry, "Holy Cross." Harold was ultimately killed in the conflict, marking the end of Anglo-Saxon rule in England.

Unresolved Mysteries

The Holy Cross may have disappeared from Waltham around the time of the Reformation, however the only other contemporary references I can find relating to the cross are in connection with King Harold, I haven't found any later sources. Did it actually exist? Also the legend mentions the smaller crucifix was sent to the local church; again it would be easy to just say it disappeared in the reformation but actually there's no other evidence it ever existed.

Historical Footnotes

Cnut, King of England 1016-1035, was succeeded by his son Harold Harefoot, son of his first wife Aelfgifu. Harold Harefoot died in 1040 and was succeeded by his half-brother Harthacnut, Cnut's son with Emma of Normandy. According the Legend of the Holy Cross, King Harthacnut unexpectedly dropped dead at Tovi's wedding feast in 1042. Confusingly, the same document says his wife in the time of Cnut (ie prior to Harthacnut's reign) contributed her gold to the installation of the Holy Cross. Was this a second wife? Or did the installation of the Holy Cross occur many years after its initial discovery? Harthacnut was succeeded by his half brother Edward (the Confessor), the son of Emma of Normandy from her previous marriage to Aethelred the Unready (King of England 978-1013 and 1014-1016.) Edward (renowned for his pious nature and the construction of Westminster Abbey), ruled from 1042 until his death in 1066.

Below: The Battle of Stamford Bridge, illustration from a 13th century copy of Matthew Paris's 'Life of King Edward the Confessor'.

The Old Chapel on Ham Hill

In A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 3 it says that in 1535 there was a chapel on Ham Hill dedicated to the Holy Cross; oblations offered there belonged to Montacute priory as owner of Montacute rectory. It probably stood near the Prince of Wales inn, where a piece of land was called Hanging Chapple in 1666, and Ham Chapel in 1840. Its connection with Montacute may suggest an association with the fair on Ham Hill given by the count of Mortain to Montacute priory c. 1102. There is no evidence of any association with Montacute's legendary Holy Cross.

The Origins of the Legend

The legend of the Holy Cross is recorded in the Waltham Chronicle, which survives in two early copies of the original manuscript. These are the 13th Century Cotton manuscript, Cotton Julius D. VI fos 73-121 to be precise, and the 14th Century Harley manuscript, Harley 3776 fos. 25-62 (http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=harley_ms_3776_f024v). Leslie Watkiss and Marjorie Chibnall, authors of a 1994 translation (published by Oxford Medieval Texts) reckon the Cotton manuscript was transcribed around 1210-1230, and the British Library date the transcription of Harley 3776 between 1345 and 1360s. The manuscript Harley 3776 was originally bound with Harley 3766 and may even include pages from the ‘Liber Niger’ that was discovered with the Holy Cross in Montacute? -the manuscripts were originally owned by the Augustinian Abbey at Waltham. The Cotton collection was accumulated between approx. 1590 and 1700 by the politician Sir Robert Bruce Cotton and his descendants, while the Harley manuscripts were collected between approx. 1680 and 1740 by the 1st and 2nd Earls of Oxford. The quirky numbering system for the Cotton collection relates to the location of the manuscripts in Sir Cotton’s original library; each of the 14 presses containing the manuscripts had the bust of a classical figure on top, so the reference Cotton Julius D.VI fos 73-121 tells us these pages were originally kept on shelf D, 6th manuscript from the left, in the press beneath a bust of Julius Caesar; the Lindisfarne Gospels were Nero D.IV!

The Cotton and Harley collections of manuscripts, along with the Sloane collection, were the founding collections of the British Library in 1753, and digitised copies of the Harley version of the Waltham Chronicle along with translations and provenance of the manuscripts can be viewed online in the Archives and Manuscripts section. The most recent and authoritative interpretation of these manuscripts seems to be The Waltham Chronicle (ed. Watkiss L and Chibnall M 1994) which includes the Latin text and the English translation as well as many notes, but prior publications include The Foundation of Waltham Abbey: The Tract 'De Inventione Sanctae Crucis nostrae', pp. xxxi-xxxii, 1-44 (William Stubbs, 1861, Latin, collation of the text of Harley MS 3776 ff. 43r-62v), and William Winters, 'Historical Notes on Some of the Ancient Manuscripts Formerly Belonging to the Monastic Library of Waltham Holy Cross', Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 6 (1877), 203-66 (pp. 228-30); (https://www.jstor.org/stable/3677989). See also The History of the Ancient Parish of Waltham Abbey, or Holy Cross by W. Winters, Williams, 1888.

J.P. Carley in ‘Glastonbury Abbey and the Arthurian tradition, ch. XVII,’ notes that the story of the Holy Cross and the kudos gained by the church at Waltham may have prompted the search for King Arthur’s grave at Glastonbury. The links between Glastonbury and Montacute continue with the story that Joseph of Arimathea, whom legend says built the original church on Glastonbury Hill, brought a Nail from the True Cross from the holy land and was buried with it on St Michael's Hill in Montacute, the nail being subsequently found and sold (as described in ‘The Particular Description of the County of Somerset, drawn up by Thomas Gerard of Trent, 1633', ed by Revd E H Bates. 1900).

Supporting evidence

There is a surprising lack of evidence for the existence of a Holy Cross at Waltham! Waltham Abbey's town history website tells us Waltham church at was consecrated in 1060 and given to Durham See after the conquest (Durham's secular canons were replaced by Benedictines in 1083; does this give us the link to Montacute's Cluniac priory, which also followed the Rule of St Benedict?). The town history website tells us Waltham church profited from pilgrims visiting the Holy Cross, and was expanded in the early 1100’s. The secular canons continued until 1177, when (as part of his penance for the murder of Thomas a’ Becket) Henry II founded an Augustinian priory, and the church was granted the status of Abbey shortly afterwards. This was when the manuscript describing the history of the Holy Cross was written. However I can find no other records that even describe a Holy Cross at Waltham, and certainly there is no record of it after the destruction of the priory during the reformation. I would love to hear about early references to the Holy Cross!

What about the site where the Holy Cross was found?

A small trench opened on St. Michael’s Hill in 1989 showed the presence of masonry walls but these probably belonged to the subsequent medieval chapel (Somerset EUS; an archaeological assessment of Montacute; Richardson 2003.)