George Mitchell, Skeleton at the Plough, 1827-1901

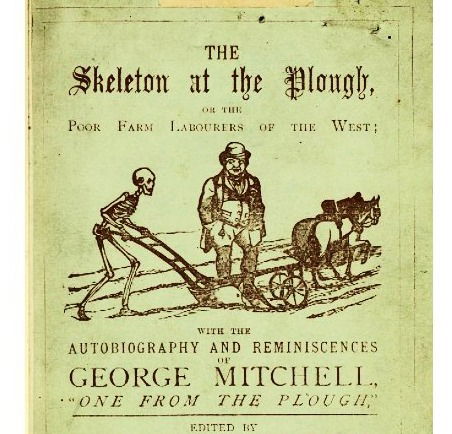

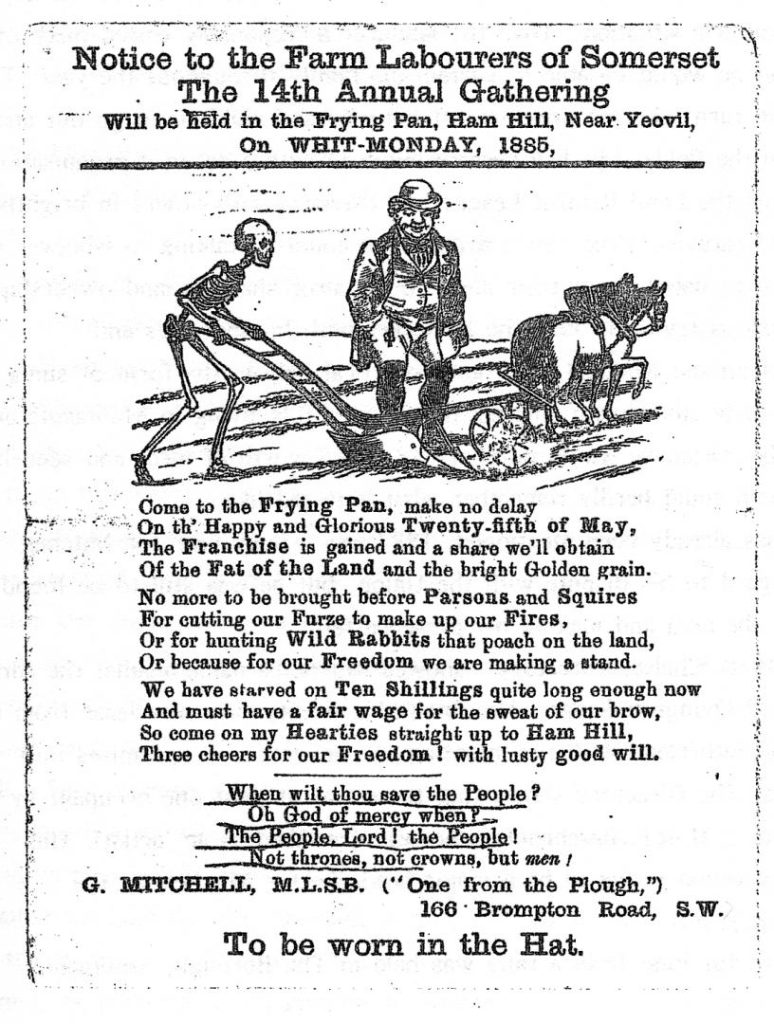

Image shows the title page of a handbill announcing Labourers' Meetings in Somerset and Dorsetshire; it was used on the cover of George Mitchell's 1874 autobiography 'The Skeleton at the Plough: or, The poor farm labourers of the West, with the autobiography and reminiscences of George Mitchell, "One from the Plough" edited by Stephen Price'.

Photo below "UP THE WORKERS" taken from the South Somerset 2021 Heritage Calendar, with gloves made for the 1951 'Festival of Britain' and a pamphlet in the foreground. The legend states "demonstrators gather in Stoke sub Hamdon on their way to join a rally supporting George Mitchell of the National Agricultural Workers Union, at the “frying-pan” at Ham Hill, around 1910." (George Mitchell died in 1901 so maybe he is mentioned because they were supporting the cause he was associated, with, otherwise the photo could be earlier than stated?)

The early years of George Mitchell's life in Montacute were wretched; born during the reign of George IV and living through the reigns of William IV and Queen Victoria, he and his family were were starving so George started work in around 1831 at the age of 5, and was regularly beaten and mistreated by his employers. (The local 20th Century author Llewelyn Powys records Montacute's 19th Century psalmist and poet, Thomas Shoel as having lived in "a small yard to the east of the Montacute Borough. In the old days this yard was called Hallet's Yard, and it was within its precincts during the reign of Queen Victoria that Ellen Mitchel, the mother of the 'Man from the Plough,' brought up her family.")

As stated on the Tolpuddle Martyrs website, "The South West farm labourer was amongst the poorest in the country. George Bartly in his report, The Seven Ages of a Village Pauper (1874) described Dorset, Wiltshire and Somerset as competing to be the worst. The South West generally was a region of “wholesale neglect’. Housing conditions were appalling."

In Mitchell's book he writes “I know of my own knowlege that I was ‘growed’ in the aforesaid village, and ‘dragged up’ pretty hard”. He describes his stonemason father having “a love of cider” and says “I was brought up in the greatest poverty and misery, just about on a par with the wretched ploughmen's families in the village”. He started work at age 5 “with scarce any clothes”, keeping rooks away from the seed corn. He says he often found his parents “so irritable from privation, that they would send me to bed without my supper as a pretended punishment, when, in reality, they had no food for me”. He commonly foraged the hedgerows for food, including snails which he would roast.

Below: Wooden bird-scarer rattle photographed at the Museum of Somerset in March 2023, described as c. 1900 from an unknown Somerset location; the caption says young boys often used wooden rattles to scare birds from crops and sometimes sang songs like "Shoo all the birds, shoo all the birds, I'll up with my clappers, I'll knock thee down backers, Shoo all the birds".

At the age of 19, fed up with starvation wages and abuse, George Mitchell went from being an agricultural labourer to stone-sawing at Ham Hill quarry. He found the cider-drinking culture there hindered any further progress so he worked his way through the poverty traps of picturesque rural villages, honing his masonry skills. He made his way to London where at the age of 23, in rebellion against his upbringing, he learnt to read and write. In his words "the clergy and gentry of my neighbourhood intended that I should be a slave all my days, and denied me the greatest happiness of life, KNOWLEDGE."

Involved with the Methodist church and living a sober and Godly life he managed to achieve the prosperity he had hoped for with his own stonemason's yard; this gave him the opportunity to work towards improving the plight of his family and the Montacute labourers he had left behind. This was at a time when the Temperance movement in the UK was becoming well established, often through the efforts of Nonconformist churches.

George Mitchell's book 'The Skeleton at the Plough' is a surprisingly good read and the themes are interesting and easily understood. Mitchell (known as 'the man from the plough') describes how the living standards of rural labourers were eroded by greedy landlords; the Reform Bill of 1832 and the repeal of the Corn Laws finalized in 1849 should have improved the lot of agricultural workers but profits were not passed on to them. Then by 1850, when Mitchell was in his mid-20s, the new railway network had made it easier to take perishables from the countryside into the cities, so landowners increased their profits and out-priced the locals on these goods, making them pay "town prices out of village wages".

Mitchell's witty observations are easy to relate to; his book starts: "We don't propose going back further than Adam who is alleged to have been first a horticulturist and then an agricultural labourer, and who, with that fatherless girl Eve formed the first union ever heard of, nor will we say much about these poor but dishonest parents of ours who lost a very good place through apple-stealing, since being orphans with neither father nor mother to tell them better, we can make every excuse for them;........"

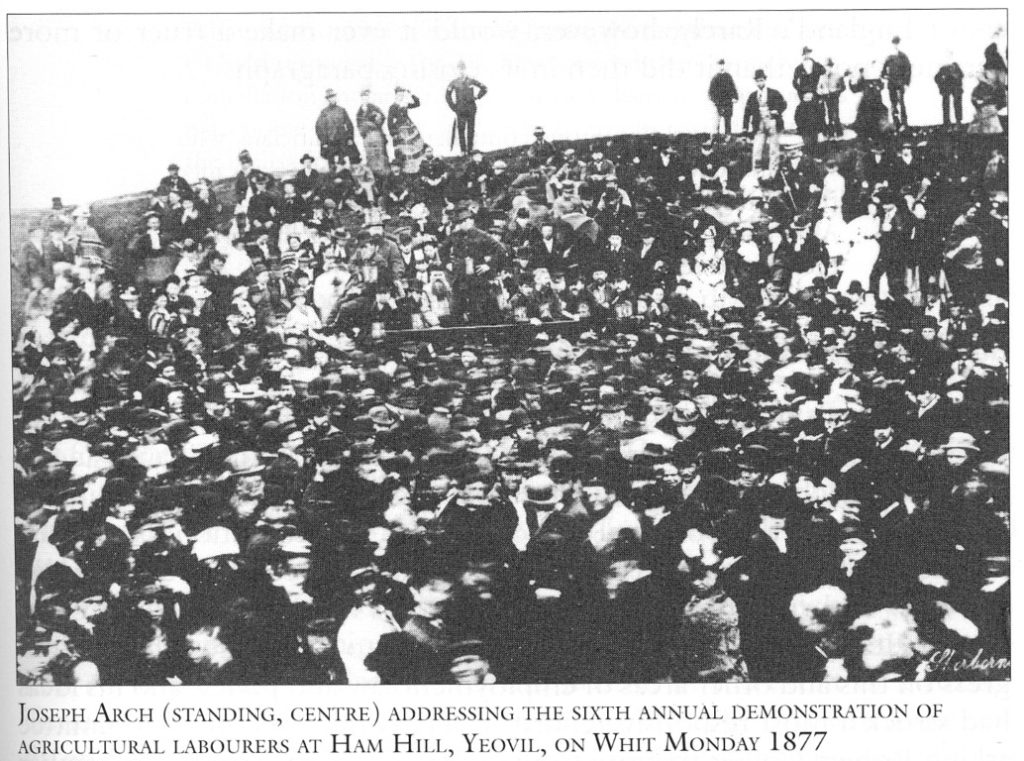

After presenting the events leading up to the dire plight of agricultural workers in his own lifetime, and giving plenty of examples of the horrendous lives and accepted deprivation of these sorry families, Mitchell describes the formation of the Agricultural Union by his contemporary, Joseph Arch (1826-1919). Born into a farm labourer's family in Warwickshire, Arch had a comparable upbringing to Mitchell's, and with the support of his wife, travelled for work and improved himself. Becoming a Methodist preacher, Arch was able to speak up for farm labourers, founding the National Agricultural Labourers' Union in 1872.

Mitchell's own life story is then presented in his book, describing how he came to join this rapidly-growing National Agricultural Labourers' Union. He describes the first Union meeting in Montacute on 4th June 1872 where he and other speakers addressed a gathering of around 1,500 attendees, and a subsequent meeting on Ham Hill in 1873 arranged by himself and also attended by Joseph Arch, which attracted a crowd of 20,000. The Ham Hill event became an annual gathering of farm workers until 1892 when Mitchell spoke for the last time. The Skeleton at the Plough was written in 1874, but clearly the strategies for empowerment of labourers were already being put in place.

The book 'One from the Plough: The life and times of George Mitchell by Brendon Owen (Gazebo Press, 2001) places Mitchell's autobiography into the wider social setting of the time and is a great read for anyone wanting to delve deeper into the history of this inspirational son of Montacute.